The fiddle traditions of the British Isles passed into North Carolina with the first white settlers. There is evidence of fiddle conventions in the Southern colonies as early as the 1720's. In the mid-1800's, a cultural swap that was to influence the history of Southern fiddle music occurred. Black slaves brought with them to American the prototype of the banjo. To this instrument they added the fiddle. There is written evidence of Black string bands providing music at white dances, particularly in the plantation environment, such as Mordecai in Raleigh.

Around 1830 or 40, the banjo passed into the white music culture and what is now called the old time string band was born. The fiddle-banjo combination remained the essence of the string band until the easy availability of the Spanish guitar from mail order houses made the guitar a basic string band instrument.

The string band provided the music for the circle and square dances that were the most popular social entertainment in rural North Carolina until the introduction of the television. This basic dance tradition had begun to change in the 1920s, however.

The popularity of the record player attracted the infant recording industry to "hillbilly recordings." In fact, the industry's first million dollar seller was "The Wreck of the Old 97." Written lyrics then became an important element of the once all-instrumental dance tunes of the string band.

In the string band "revival" of the second half of the twentieth century, which is still growing and gaining strength today, perhaps no musicians have been as widely influential and popular as those from the area between Mount Airy, North Carolina, and Galax, Virginia.

Hundreds of recordings by musicians from this region have caught the ear of old-time music fans around the world, who in turn come to the Mount Airy and Galax fiddle conventions by the thousands every year, and aspire to the region's distinctive sound.

Even more important to the vitality of this music is the way people born and raised in the area continue to treasure it. WPAQ has broadcast live, local string band music out of Mount Airy since 1948, and countless bands on both sides of the state line continue to play and transform the music that their ancestors loved.

The string band music of the Mount Airy - Galax region is not so much one cohesive style as a mosaic of musical and familial legacies, closely interrelated but highly varied. Certain hallmarks define this as a regional style, like powerful blues influence in both rhythm and melody, and a blurring of the line between bluegrass and old-time styles that can give rigid musical taxonomists fits, but that makes for a powerful and exciting band sound.

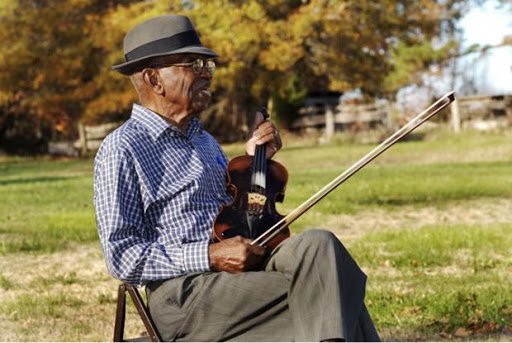

This is also a region of great musical innovation, where individual artists and bands have, over the course of the last hundred years, pioneered styles that continue to influence old-time musicians today - the gentle heart songs of Ernest Stoneman and his family, and Eck Dunford, recorded in the 1920s and '30s; the elegantly filigreed bowing of fiddlers Emmet Lundy and Luther Davis; Kilby Snow's passionate "double-clutch" autoharp picking; Tommy Jarrell and Fred Cockerham's tight fiddle-banjo duets, as syncopated as the best funk tracks; the hard driving dance tunes played around Orange and Alamance Counties by Joe Thompson (pictured left); the wildly careening full-band sound of the Smokey Valley Boys and the Camp Creek Boys.

Old-time music is a thriving art form in and around the North Carolina Piedmont. Nearly every day of the week you can find friends getting together to "share tunes."

Old Time Music & Dance

Dancing has always been an important part of the old time music tradition. Called square dances, team clogging, flatfooting, buck dancing and contra dances are fueled by old time fiddle tunes. As with old time jams, square dances are a place where strangers meet and form community.

Shape Note Singing

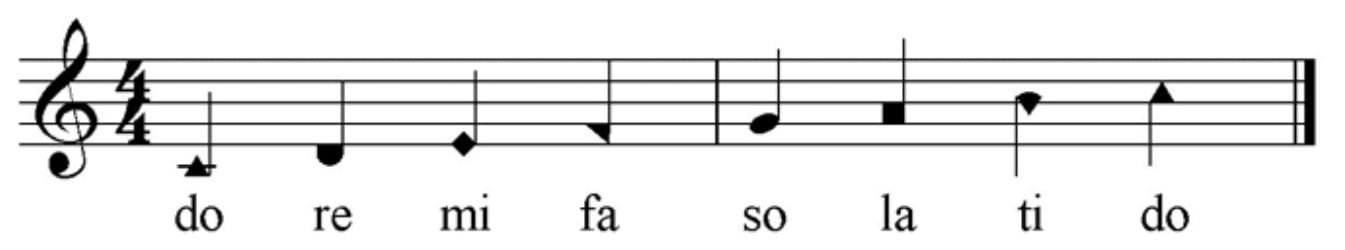

Shape Note Gospel is a Southern rural tradition. It's often included at old time music camps, fiddlers conventions and gatherings around North Carolina.

Originally designed in order to teach largely illiterate congregations from song books, shapes were substituted for notes on the staff and the melody was sung "by the shapes" before putting the words into song. The songs are sung a cappella, without accompaniment, with four distinct parts - tenor, bass, treble, and alto.

The Sacred Harp book was first published in 1844 and continuously updated since then. Its tunes are folksy in nature and the words frequently come from 18th century hymn writers such as Isaac Watts and Charles Wesley. The book includes more than 500 hymns, odes, and anthems, with most of the texts religious in nature. The term "sacred harp" is a poetic reference to the human voice.

Shape note singing is a participatory art form, not intended as performance for an audience. At a shape note gathering, singers sing for each other and for the joy of singing. Singers in this tradition sing without accompaniment and sit arranged by vocal part in a hollow square. The "hollow square" is divided into four parts.

Men or women can sing any part. The melody is always in the tenor. These singers don't formally rehearse or perform; they sing to each other. They can see all the faces of their friends and hear all the harmonies. Whoever wants to can call a tune, and everyone turns to the page.

Shape Note tunes are sung at full volume in an exuberant outpouring of sound and feeling. The rich 3- and 4-part harmonies fill the room and pull those participating together in a deep way.